-----------------------------------------------------<{}>------------------------------------------------------------------

Isaac Cryle Decker was the fifth child of Isaac Decker Sr. and his first wife, Deborah. Family Search gives Isaac's birth date as February 18, 1829 and death date as Between 1874 - 1876, but I'm uncertain of their sources for this information. Census data confirms the year of birth (1829) and gives his birthplace as "Upper Canada." This did not mean that he was born in the northernmost reaches of the Canadian border. The phrase "Upper Canada" was used by early Americans to designate an area along the "upper" (or western) portion of the St. Lawrence River. This included the area around the northern borders of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. The "upper" portion being "up river" from the lower (or eastern) portion, was what made early settlers call the southernmost part of the modern Province of Ontario "Upper Canada."

Isaac may have indeed been born in Ontario, Canada, however it is also possible that he was born in Michigan, near Detroit. Lizzie Decker (his daughter), in the 1900 Census, said that her father was born in Michigan. Isaac Decker Sr., Isaac Cryle Decker's father, purchased a couple of large tracts of land in Michigan in the early 1830s, so he may have been a resident in the state prior to 1830, when Isaac Cryle Decker was born. Since Michigan was a Territory at this period of time (from 1805 to 1837), not yet a state, and had been within British jurisdiction, it may still have been considered as part of Upper Canada.

Isaac Cryle Decker moved to Texas with his family about the time his father had qualified for a league of land (4,228 acres) in Ben Milam's colony on 17 Mar 1835 (present day Travis County). A few years later, due to trouble with Indian attacks, Isaac Sr. sold his Milam County land, and was granted a labor of land (177 acres) in Montgomery County, Texas. One can only imagine the terror that drove the family to abandon their newly built home and move to a more populous area, but it must have been a hard decision to make.

Isaac Cryle Decker can be found in the 1850 Census living with his father and his step-mother (Isaac Sr.'s second wife Ann), in Montgomery County, TX. Though he is listed in his father's household, he has $600 worth of acreage of his own. He also shows up on the tax lists for Montgomery County from 1850 through 1873 when there is a break in the tax list. His family lived in the vicinity of Tillis Prairie, in Decker Prairie which his father founded. Decker Prairie is now an unincorporated rural district of homes, with an elementary school, and community center, and it still retains the pioneer family's name. The old cemetery where Isaac Decker Sr. and his family are buried is still intact.

|

| 1850 Census: Isaac C. Decker, in his father's household, Montgomery County, GA. |

Isaac married Rachel Elizabeth Sanders, daughter of Claiborne B. and Nancy (Holder) Sanders, in Montgomery County TX on 26 Dec 1855. They were married by Lemly Clepper, a justice of the peace.

They had the following children:

1) Almira Elizabeth Decker b. 10 Jan 1857 Montgomery TX, d. 1 Nov 1913 Brownwood, Brown, TX; m. James Andrew Gilley 3 Feb 1875 Waller, TX

2) Ophelia Jane Decker b. 20 Sep 1859 Montgomery, TX; d. 15 May 1939 Hageman, Chaves, NM; m. Andrew Austin Andrus.

A quote from the 1974 Decker Prairie Year Book states that 'This family lived in Decker Prairie for awhile but possibly moved "back north" in later years.' The fact that the couple do not appear in the 1860 Federal Census in Montgomery County might explain the speculation. However, we know from Montgomery County tax lists that they lived in the area from 1850 through 1873, since Isaac C. Decker is listed as a neighbor to his father up to his father's death. We also know that Isaac and Lizzie were in Texas for the Civil War.

Isaac was not only in Texas during the Civil War, he enlisted in the Confederate Cavalry on 14 May 1862, as a Sergeant in Waller's Regiment, Company D, 13th Battalion. He served until the end of the war.

Isaac was not only in Texas during the Civil War, he enlisted in the Confederate Cavalry on 14 May 1862, as a Sergeant in Waller's Regiment, Company D, 13th Battalion. He served until the end of the war.

Name:

Isaac Decker

Side:

Confederate

Regiment State/Origin:

Texas

Regiment Name:

Waller's Reg't Texas Cavalry

Regiment Name Expanded:

Waller's Regiment, Texas Cavalry

Company:

D

Rank In:

Sergeant

Rank In Expanded:

Sergeant

Rank Out:

Sergeant

Rank Out Expanded:

Sergeant

Film Number:

M227 roll 9

[National Park Service. U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865 ]

In the March 1862 edition of the Houston

History has been rewritten to reflect only the Union side of the Civil War. If you read the Wikipedia article, for example, it fails completely to reflect the southern side at all. They have insisted the war was about ending slavery. That was only a small part of what the war was about, and for most soldiers (both North and South) was not significant at all. Indeed, the emancipation of slaves was not even made an explicit part of the war effort until the Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on 1st January 1863.

The North was largely an industrial economy, which gave them an advantage in liquid assets. They were also more populous, which gave them an advantage in votes in congress and for the presidency. When congress met to decide issues involving all states, the North had become dominant in every major issue. The South began to feel that they were being unfairly taxed to support causes that benefitted only the North. It was a situation of taxation without representation. The North continued to increase taxes on land, crippling the Southern economy, in order to build infrastructure in the North. The situation was rife for contention. The South decided that the only way that they could maintain their rights of representation in congress was to secede from the union and form their own nation. This was the real initiating cause of the Civil War.

“Regiment of Mounted Men for three years or the war, were at home on horseback, who ride like cowboys, who hit the bull’s eye with a rifle or pistol, and go anywhere and stand anything like a regular Ranger. Recruits are requested to bring their Arms when they have suitable Guns, Pistols, etc. . . . They are also requested to bring their Horses . . .

Texians your homes and hearthstones are now threatened from the North. You are called to the rescue . . . Come now, come at once, come to the rescue and let us win our liberties by our valor. Here is a service that Texians delight in. This Regiment like the brave Rangers of Terry’s [8th Texas Cavalry] will be assigned duty in the teeth of danger. Come with me, and I will lead you right when your habits and disposition will enable you to make the best fight in your power.”

Waller was warning men that their "homes and hearthstones" were threatened by a northern invasion. The Union Army was threatening to invade Texas by way of Arkansas and Louisiana which they were in the process of conquering. Isaac C. Decker was among the men who answered the call. An army was invading his homeland, and threatening the peace of his family. Isaac owned no slaves, and did not fight for the cause of keeping slavery. He was fighting for the right of his state to determine their own future. He readily signed up for Waller's regiment.

It was on 7 Sep 1862 that they had their first encounter with the Union army at Bonnet Carre. Things went badly for the Confederate Cavalry there; and, along with most of the other men, Isaac lost his horse and was forced to regroup with the rest of the battalion several miles away. The following is a voucher reflecting that Isaac lost his horse and his gun, as well as other equipment, in that retreat.

Union Major General Benjamin Butler became angry at reports of the depredations that were being caused by Confederate forces. He became determined to put an end to it. However, the event that finally galvanized him into action actually had nothing to do with Waller's Regiment. It was an attack on the 8th Vermont Infantry, that was the responsibility of Confederate General John Pratt, who was in charge of the Louisiana militia. Pratt had ignored a white flag of truce, and attacked the Vermont Regiment, taking many prisoners.

General Butler mistakenly attributed this cowardly act to the Texans, instead of the Louisiana militia. He was so angry at this injustice that he decided to launch an attack directed specifically at Waller's Regiment, in order to put them permanently out of commission. Over four battalions of Union troops were assembled near Carrollton on September 8th, 1862 to begin the assault. The Confederates were outmanned six to one, and the Union army also included two battalions of artillery of which the Confederates had none. The result was a disaster for Waller's men.

William Craig, a Confederate soldier with Waller’s Regiment, wrote the following:

“They saw the boats leave Carrollton about 1 o’clock at night and they supposed they were coming up to give us a fight and they hurried with the greatest dispatch to inform Col. Waller of the fact and reached camp about daylight. The whole command was formed in a few moments and we were marched into a cane field and here we waited until the boats had moved on us and then the transports landed their men . . . While marching on, their guard fired on our advance and killed three men . . . but they were hid in the cane and our men could not fire . . . [We] pushed on but could not find ground sufficient to form in line of battle mounted so all were dismounted and then every forth man had to hold horses. We then marched about 100 yards and all were stationed along side of the road awaiting an attack . . . then they opened on us with their Battery & Minnies and Waller gave the order to fall back to our horses amid Shells &balls! We retreated down the canal and here we come to the Swamp and Col. Waller finding it impossible to take our horses into the swamp, commanded all to leave their horses and take it afoot. Some led their horses in two or three miles but finding that they could go no further left them. By this time the command was very much scattered and in all directions. Col. Waller . . . Major Boone and almost all of the Captains had squads all day in getting through the swamps and some arrived at the station about noon and another squad arrived about sundown. All wet and hungry and remarkably tired. Some came in with no shoes on, no hats and some with hardly any clothes.”

In another account of the skirmish, a letter printed in the Bellville Countryman [Vol. 3, No. 12, Ed. 1] Saturday, October 18, 1862, William P. Jackson wrote that there were two gunboats in the river beside them “keeping opposite to us, watching our movements. This boat had two masts, on the foremost stood a man with a spyglass so that he could see all our movements and count our number…Boom came the shells all over us—bursting some fifteen or twenty inches above our heads;—doing us no damage, however, but scaring us pretty badly, and our horses worse…We now arrived at a large ditch near the swamp, which we immediately crossed and were then ordered to dismount, and one man hold eight horses.”

They walked down the ditch and through the sugar cane, before halting and assembling in preparation for a charge by the enemy line. Jackson continues, “Col. Waller walked out where he could see them, and said: ‘Boys, that line is two miles long.’ Just at this time some one came up and told him they were out-flanking, and getting between him and the swamp. He then ordered us to get to horses. Just as we started they commenced firing at us with four pieces of artillery."

A more official account was published in the Tri-Weekly Telegraph (Houston, TX) [Vol. 28, No. 81, Ed. 1] Monday, September 22, 1862:

The Boutt Station Fight: Narrow Escape of Waller’s Command

“On Sunday, 7th inst., we went to Boutt Station and took possession; but finding no water for our horses, we returned up the river about five miles, to a sugar plantation, where we seized two schooners, loaded with sugar and molasses which we burned. On Monday, the 8th, at daylight, there appeared four transports and the man-of-war Brooklyn, about four miles below, coming up. We saddled up and returned into the sugar field, where we waited until two of the transports landed below us, and the other two at once came on up and landed about two miles above us, and put off about 1500 infantry, and two batteries of artillery, which at once formed and came forward into the cane-field just above us. We struck down nearer the swamp, and attempted to move up the river, when suddenly our advance was fired upon, killing three or four men. We then retreated to the rear of the sugar field, and between it and the swamp. the Brooklyn was shelling us heavily the whole time. We first formed on horseback, but found the ground unsuited for cavalry charge,—We then left our horses and went forward on foot, when the enemy suddenly fired on us from ambush, attacking both flanks with shells, grape, canister and musketry. We stood our ground firmly, expecting the enemy to advance, until we observed a force striking between us and the swamp, with the intention of surrounding us; and at the same time discovered the number of the enemy to be much greater than we at first thought—1200 or 1500 more moving upon us from the transports which had landed below. Major Boone at once ordered a retreat to the swamp, which most of us reached, with our horses, under heavy fire. After getting into the swamp, Major Boone and Col. Waller concluded that the only alternative was to surrender, or leave our horses and try to make our escape through the swamp on foot. We chose the latter; and after some delay, during which time we were shelled incessantly, we started on our way through the swamp. On Tuesday, the 9th, near night, after terrible suffering, we reached the camp, on Bayou Desalmarede, with only 140 men, since which one 50 others have arrived at Thibodaux. Our whole number which went into the fight was about 250 men. The enemy had about 3,000 infantry and artillery, and 500 cavalry. Some of our missing may yet turn up. T. Hensly, A. Q. M.”

The Union troops pursued the Confederates, coming across about 300 horses mired up to their bellies in mud. Some of them had fallen in trying to extricate themselves, and had been empaled by Cypress knees growing out of the mud. The Union soldiers continued to pursue, shooting at the retreating men until they had captured the few who were within their firing range, but they soon realized that it was useless to continue further.

Waller's Regiment regrouped, and camped. After careful consideration, Waller allowed one man from each company to return to Texas in order to gather weapons and horses to resupply the men. In the meantime, most of the regiment were ferried about in cane carts from camp to camp. The Union soldiers began to call them the "cane cart company," adding to their humiliation. Waller's Battalion was effectively taken out of the fighting for the rest of the year, while they waited to be resupplied.

A severe early winter took its toll on the troops through illness late in 1862, typhoid fever, pneumonia, and tuberculosis broke out in epidemic proportions among the weakened troops, and two men died from exposure in the blasting winter chill. Fortunately, new supplies reached them before they had lost many men. These supplies included tents, blankets and warm clothing as well as fresh food. The rest of the winter was milder as well, so that they were able to get through without further losses.

By Spring, the 13th Battalion was equipped and ready to join the fighting. They were anxious to overcome the enemy, to prove that what happened at Bonnet Carre had been merely a temporary setback. In April of 1863 they were ordered to engage the Union forces to offer relief to Vicksburg, which was under siege. In order to do so, they would storm Fort Buchanan where enemy supplies were being delivered.

They had to cross a lake, twelve miles long, in flimsy skiffs, then slog through several more miles of waist deep swamp during the middle of the night, before reaching the enemy. The following clipping gives an account of the storming of the enemy encampment:

|

| Dallas Herald. (Dallas, Tex.), Vol. 11, No. 33, Ed. 1 Wednesday, July 15, 1863. |

Their reputation made good, they continued to encounter the Union army north of Vicksburg and skirmished with them at Bunch's Bend, where they captured many prisoners as well as supply wagons. On 9 June 1863, they encountered the Union army again at Lake Providence, but the battle was indecisive.

There were no further encounters that year, and the men finally settled into winter quarters. In the following spring they had their worst encounter yet with the Union forces at the battles of Mansfield on 8 April and Pleasant Hill on 9 April in 1864. The Union forces retreated, and the Confederates followed them north to Jenkin's Ferry where they engaged them in battle again. Things went badly for the Confederate forces there, but the battle was indecisive. This was the final battle that the 13th participated in. They were stationed again in Louisiana and Arkansas where they were involved in building bridges and patrolling river routes, before returning to Texas. The entire battalion was on leave just before the war ended.

Isaac went back to his farm, and continued to live on Decker's Prairie until his death. He appears in the 1870 Census in Montgomery County, Texas.

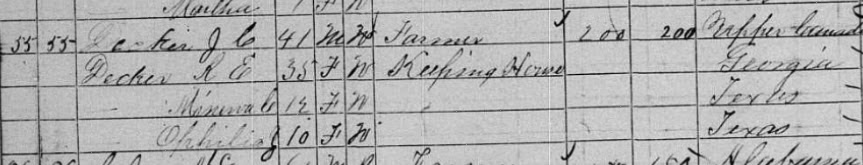

|

| Isaac C. Decker in 1870 Census, Montgomery County, TX |

I have yet to locate a cemetery record, obituary or probate records to confirm his death date, but former researchers have his death in Sep of 1873. There may be a grave marker for him in Decker's cemetery that has yet to be transcribed. If he did die in 1873, he was still quite young at the time, at just 44 years of age.